This is a reminder that the final exam will be in Quigley room 203 at 10:10am on Monday. Please arrive with pen and paper, as well as a copy of your Mercury Reader.

Snow Day

We will not be meeting today due to the University’s closure. Therefore I am asking that you email your portfolio to me, and if that is not possible bring it with you to the final exam. If you email the portfolio I will have your estimated final grade (minus the 10% from your exam) calculated and ready for you on Monday and your portfolio grade will be posted to D2L before that. Also if you email the portfolio do not worry about scanning your original drafts–simply bring them with you to the exam and I will confirm the points I credited you for them.

Everyone be safe and enjoy the snowy weekend!

final portfolio

THE FINAL PORTFOLIO IS DUE THIS FRIDAY.

Your portfolio must be bound in some way: brackets, binder, or folder. It must also be submitted to D2L to earn credit.

The portfolio should contain:

1. Your reflective introduction

2. A revised Unit Two essay

3. Two additional revised essays of your choice

4. Your original Unit essays

Reflective Introduction and Portfolio Prompt

ENG 101: English Composition I

Unit Five Assignment Prompt:

Reflective Introduction & Portfolio

Portfolio Submission Date: Friday, 06 December 2013

Assignment:

To demonstrate your growth as a writer, your understanding of your composing processes, and your awareness of your rhetorical choices, you will compose a Portfolio of three revised and polished essays. This Portfolio will include Unit Two, along with two of the following: Unit One, Unit Three, and Unit Four.

To introduce your reader to your Portfolio—and to your semester-long development as a writer and scholar—you will compose a Reflective Introduction, which will discuss:

I. the three essays you selected, with attention to rhetorical choices you made about:

i. your initial composition of the essays

ii. your revisions of these essays (both from Rough Draft to Working Folder Draft and from WF Draft to Portfolio Draft)

iii. your reasons for including these essays

II. your development as a writer in this course, with thorough reflection upon:

i. increased skills as a writer and scholar

ii. areas to be targeted for improvement in future courses

iii. how development will serve you in future situations

Thus, in the Reflective Introduction, you will write about your own writing; and, in this process, you will show that you can “take a careful look at [your] own work to identify [your] patterns, strengths, and preferences for negotiating writing tasks, for learning new skills, and for putting those skills into practice” (Portfolio Keeping 6).

The Reflective Introduction builds upon previous writings. In Unit One, you explored an event in your life that increased your literacy education and enabled you to join a community. Here, you will explore your semester in ENG 101, an event that increased your rhetorical education and enabled you to join the community of academia. In Units Two and Three, you analyzed and evaluated the rhetorical choices of others; in this Unit, you will analyze and evaluate your own choices, writing processes, and their results. In Unit Four, you synthesized knowledge from multiple texts to assert your own claim; here, you will synthesize evidence from our entire course (i.e. essays, flashwrites, homework, readings, discussion, etc.) to support your conclusions about your evolution as a writer. Further, the Reflections completed after each Unit serves as a Unit-length example of this course-length Reflective Introduction.

Reflective Introduction Requirements

Page Length: 5-6 double-spaced pages (12-point font, 1” margins) with MLA header

The Reflective Introduction should:

- show critical engagement with and reflection upon your own writing processes

- demonstrate your ability to use college-level written communication

- have a creative, unique title and introduction that captures reader interest

- present a thesis that offers an overall evaluation your writing and development

- illustrate your writing journey through an overarching metaphor or image

- provide sufficient evidence from a variety of sources to support your claims

these sources (i.e. readings, drafts, responses) must be cited accurately - have a logical organization aided by effective transitions

- be virtually free of mechanical, grammatical, and usage errors

Portfolio Requirements:

The Portfolio should:

- open with a Reflective Introduction

- hold three revised and polished essays

- must hold Unit Two

- hold two of the following: Unit One, Unit Three, & Unit Four

- include WF Drafts and Professor Responses for each included essay

- place in an order that supports ideas explored in Reflective Intro

Revision Policy for Portfolio:

Because our course supports the theory that writing is a process occurring over time, and continual improvement is possible for all writers, the English Department strongly encourages all writers to revise the essays selected for their Portfolio.

Since our course also supports and encourages risk-taking, creativity, and invention throughout the composition process, please be advised that you will not receive a lower grade on your Portfolio Draft than you did on your WF Draft. If you choose not to revise, you will receive the same grade. If you revise in a way that some might see the essay as less successful after revisions, you will receive the same grade. Strong, thoughtful revisions, though, can only increase your grade—so, revision is encouraged!

Submission:

Portfolio Due Date: Friday, 06 December 2013

*submit (1) hard copy in class AND (2) electronic copy via D2L

*if not submitted both in hard & electronic copy, late penalty will occur

Please have completed this checklist to bring with you to our scheduled conference

Synthesis Essay Scorecard

for each question, rate yourself 0 (no), 1 (somewhat), 2 (pretty good), or 3 (excellent)

also, highlight/circle/mark the THREE questions you wish to discuss in detail during conference

Introduction:

- An introduction? __________

- Begin with an attention-getter? ___________

- Introduce your topic & gives context? __________

- Ends with a thesis that is based on synthesis? ______

Summary:

- A summary section? __________

- Objective summary for all five sources? __________

- All summaries 2-4 sentences long? __________

- First sentence of each: title, author, ethos & their thesis? ________

- Remaining 1-3 sentences develop relevant points? __________

Analysis:

- An analysis section? __________

- Discuss the main ideas shared by all 5 sources? __________

- Explores the sources’ similarities & differences? __________

- Uses quotes during comparison to illustrate?___________

Synthesis:

- A synthesis section? __________

- Explore your past feelings/thoughts on topic? __________

- Expands on your thesis by addressing a possible solution to your issue that you derived from your sources? __________

- Explore what you now feel? __________

- Throughout, are you & articles having a conversation? __________

Conclusion:

- A conclusion? __________

- Begin by restating your thesis? __________

- Connect your essay / its topic to your reader? __________

- End with a vivid scene/question/statement? __________

Sources & Citations:

- 5+ strong, relevant sources? __________

- 3+ sources from MR and 2+ from outside works? __________

- Use 1+ quote(s) from each source? __________

- Give in-text citations for every quote? __________

- When sharing another’s views, signal phrases? __________

Overall:

- A unique, creative title? __________

- MLA headers on top-left (1st page) and top-right (all)? __________

- 12-point font, 1” margins, and double-spaced? __________

- Clear, smooth transitions and almost no surface errors? __________

We have conferences scheduled for Friday (11/15) and Monday (11/18) in Faner 2238. You must come to your scheduled conference or you will receive two unexcused absences. If you did not hand a rough draft in to me today you will need to bring what you do have completed of your Unit Four essay to the conference. Also, try to have the check list that I have emailed to you completed and with you for our conference.

It’s time to get things done, so do not waste the two days that we are not meeting as a class. Get work done on your essay–schedule a meeting with the writing center, ask a friend to have a look at your paper–and keep working even if we are not set to meet until Monday. If you end up changing your draft bring in a new copy and we can go over that as well.

The final draft is due Wednesday, November 20th.

Q&A Unit Four: Round Two

How do I tie my articles together and have it all make sense? How do I unite my body paragraphs?

In order to tie your essays together you need to first find the one common topic that they all share. From there begin listing subtopics that appear in each article. You will find that some articles have similar or the same subtopics. This is a good way to go about forming body paragraphs. If you devote a paragraph to each subtopic, then compare and contrast two of your sources’ viewpoints in that paragraph, you will have united your sources and kept within the overall topic of your thesis.

An example would be that I may find that all five of my essays have something to say about coastal erosion, but they comment on this topic in different ways and at varying degrees. So then I make a list of the types of things, or subtopics, that my articles say about coastal erosion.

Article #1: cost of erosion for the country, how coastal erosion is a serious threat to communities during hurricane season.

Article #2: coastal erosion is a natural occurrence and people should simply adapt by not living near the coast, the politics of coastal erosion.

Article #3: coastal erosion is wiping out an entire fishing industry in America.

Article #4: facts and figures about coastal erosion over the last sixty years.

Article #5: what is being done to combat coastal erosion in other countries and how America could follow suit.

After making my list of subtopics I can see many ways that my articles are in conversation or synthesis. First of all article #2 is my opposing viewpoint and goes against the grain of my other articles so it can be used to show the rebuttal to my thesis. Second, article #1 and article #3 are both discussing money—for article #1 it is the general cost of erosion for the country, and for #3 it is specifically the loss we take when an entire industry is under threat. Articles 4 and 5 can both be used to reinforce my other articles and to provide context for my reader.

What if I still haven’t found any good outside sources?

It is very important that you do this sooner rather than later. If research is proving to be difficult for you then you may want to stick to Opposing Viewpoints and stay away from Academic Search Premier. Finding your sources takes effort, it will not happen in ten minutes—unless you are very lucky or willing to settle for a weak source. Take the time to look through articles based on your overall topic and the subtopics of the essays that you chose from your Mercury Reader. Ask a librarian or make an appointment with the Writing Center of all else fails.

How specific does my overall topic have to be?

Your overall topic is most likely going to be broad or very general. What you need to focus on making specific is your thesis. Your thesis should be developed from the synthesis of all of your articles. This implies that you have identified the subtopics of those articles, which are more specific aspects of your broad overall topic. So when determining your overall topic you do not have to stress about making all five sources agree on a very specific point, save that work for your thesis and how you plan to address the subtopics in each source.

How is synthesis different from analysis?

In order to get to synthesis you must analyze. When you analyze your sources you are breaking them down to observe how they work topic by topic. For our Unit Four essay this is done through comparing and contrasting sources. When you only focus on a single topic of a source at a time you are giving it close attention, thus analyzing not just what the source is arguing, but how it is making its point. The reason comparing and contrasting is used to do this is because when we place sources beside one another it is easier to observe the smaller, more specific details.

Once you have analyzed all five sources by comparing and contrasting them via subtopics, you can begin to synthesize all of that information. In synthesis you take the best ideas from all of your sources and try to make a better, relevant “answer” or claim to the problem at hand. So if you are writing about pesticides then you would read and analyze what all five of your sources have to say about that and from there choose the best approach to dealing with pesticides based on what all of the sources had to offer.

Homework for Friday

To begin your body paragraphs I would like you to draft 6 topic sentences for your analysis portion of your paper and 3 topic sentences for your synthesis. This should be emailed to me by class time Friday.

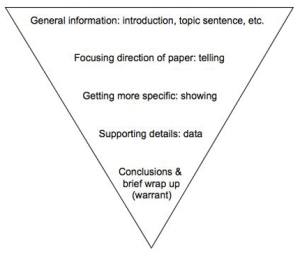

A topic sentence is a general introduction that gives a reader the main idea or subject of the paragraph that follows. In terms of the organizational pyramid, your topic sentence is the most general part of your paragraph. From the topic sentence you move toward specificity with your claim, evidence, and tie-in to the thesis.

Even if you are unsure of where your essay is going right now, try to form your topic sentences based on the subtopics of your paper so that each paragraph is exploring a different part or facet of your overall idea/thesis.

Example)

“Stereotype threats are discussed in depth by Claude M. Steele in his two articles that make up “The Many Experiences of the Stereotype Threat.” Through several social experiments, Steele has determined that the mere threat of a stereotype is all it takes for an immediate negative turn in someone’s performance. “No special self-doubting susceptibility seemed necessary” for a stereotype to have an effect (Claude 253). These effects also involve the way a person views others and identifies them.

From reading the topic sentence of this paragraph (as seen in italics) we come away with a general idea of what is to be talked about (stereotype) and in what way (via Steele’s articles). As simple as it is, this writer’s topic sentence has successfully prepared the reader for all of the information that is to come in the rest of the paragraph.

Writing Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid – The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: Transition, Topic sentence, specific Evidence and analysis, and a Brief wrap-up sentence.

- A Transition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand off from one idea to the next.

- A Topic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific Evidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A Brief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument:

Facts:

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

Deduction

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

- Conclusion

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

Socrates

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

Lincoln

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage, clear purpose, and great), the connections get tenuous.

Rebuttal Sections

In order to present a fair and convincing message, you may need to anticipate, research, and outline some of the common positions (arguments) that dispute your thesis. If the situation (purpose) calls for you to do this, you will present and then refute these other positions in the rebuttal section of your essay.

It is important to consider other positions because in most cases, your primary audience will be fence-sitters. Fence-sitters are people who have not decided which side of the argument to support.

People who are on your side of the argument will not need a lot of information to align with your position. People who are completely against your argument—perhaps for ethical or religious reasons—will probably never align with your position no matter how much information you provide. Therefore, the audience you should consider most important are those people who haven’t decided which side of the argument they will support—the fence-sitters.

In many cases, these fence-sitters have not decided which side to align with because they see value in both positions. Therefore, to not consider opposing positions to your own in a fair manner may alienate fence-sitters when they see that you are not addressing their concerns or discussion opposing positions at all.

Organizing your rebuttal section

Following the TTEB method outlined in the Body Paragraph section, forecast all the information that will follow in the rebuttal section and then move point by point through the other positions addressing each one as you go. The outline below, adapted from Seyler’s Understanding Argument, is an example of a rebuttal section from a thesis essay.

When you rebut or refute an opposing position, use the following three-part organization:

The opponent’s argument: Usually, you should not assume that your reader has read or remembered the argument you are refuting. Thus at the beginning of your paragraph, you need to state, accurately and fairly, the main points of the argument you will refute.

Your position: Next, make clear the nature of your disagreement with the argument or position you are refuting. Your position might assert, for example, that a writer has not proved his assertion because he has provided evidence that is outdated, or that the argument is filled with fallacies.

Your refutation: The specifics of your counterargument will depend upon the nature of your disagreement. If you challenge the writer’s evidence, then you must present the more recent evidence. If you challenge assumptions, then you must explain why they do not hold up. If your position is that the piece is filled with fallacies, then you must present and explain each fallacy.

Notes on structure

Overall Structure of the Essay:

Intro: attention getting, introduces the issue/problem, ends with thesis

Summaries: 2-4 sentences for each article. The first sentence should always contain the source’s author and title. Summaries should be concise and only cover material relevant to your thesis/argument.

Analysis: comparing and contrasting your sources in the context of your thesis. Break your sources down and discuss how the pieces work alongside each other.

Synthesis: Mentioning favored viewpoints from your sources, formulate your evolved understand of the overall subject.

Conclusion: restate the thesis, discuss the big picture in light of reviewing your sources and synthesizing, leave the reader thinking.

Structuring Your Introduction:

(1) Open the essay with a creative imagining or statement that address the reader.

(2) Move into context of the subject being discussed. This is where you give the reader the status quo.

(3) From the context give your reader a reason to invest in this subject.

(4) Present your thesis.